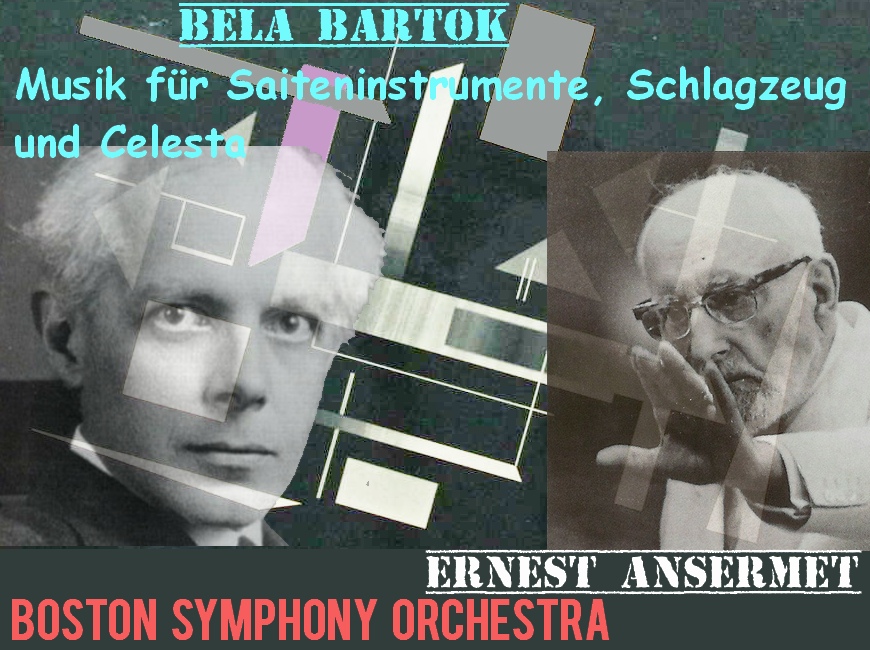

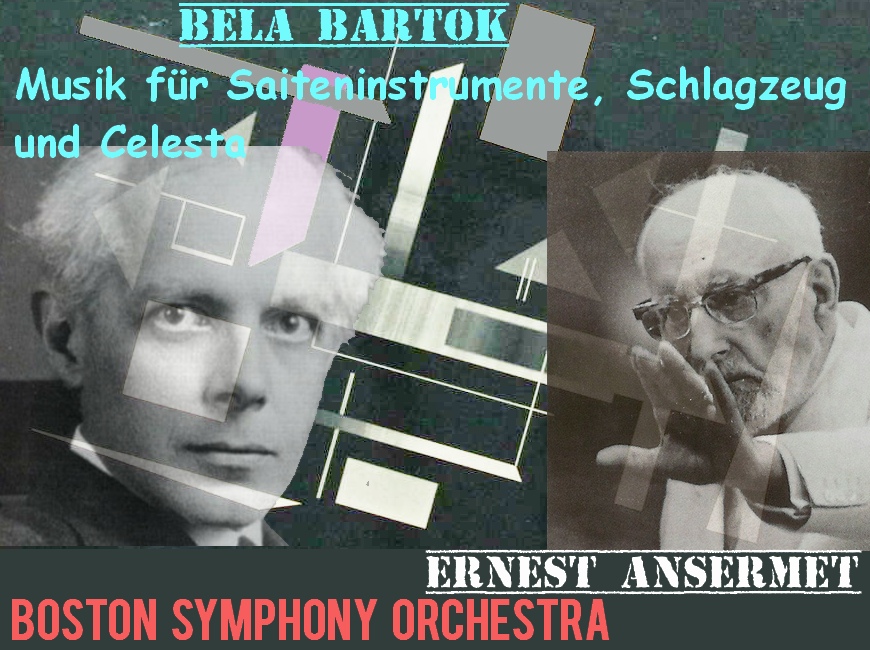

Béla BARTOK

Musique pour cordes, percussion et célesta, Sz 106

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Ernest ANSERMET

31 décembre 1955

en complément, sur la musique moderne:

a) Ernest Ansermet, 12 novembre 1951

b) Ernest Ansermet et Arthur Honegger, 30 mars 1947

Ernest ANSERMET aux USA de fin décembre 1955 à la mi-janvier 1956...

Un court entrefilet dans la Tribune de Genève du 23 décembre 1955, page 10, annonçait "[...] Le chef de l'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, le maître Ernest Ansermet, est parti hier à 17 heures en compagnie de Mme Ansermet, pour New-York, à bord de l'avion de la Swissair. Le maître restera deux semaines à Boston, où il dirigera plusieurs concerts avec l'Orchestre philharmonique de cette ville. Puis toujours avec cet orchestre, il donnera des concerts dans diverses villes des Etats-Unis, pour terminer en donnant deux concerts à New-York. Le maître rentrera le 15 janvier. [...]"

Dans le «The Boston Sunday Globe» du 25 décembre 1955, en page 30, fut publiée la courte présentation suivante:

"[...] VISITOR FROM SWITZERLAND — Ernest Ansermet has arrived in Boston to prepare for a two-week stint as guest conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He will direct his first program at the concerts of next Friday afternoon and Saturday evening.

Ernest Ansermet Symphony Guest

Ernest Ansermet, who has just arrived in this country from Switzerland to be the guest conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, will lead the concerts next Friday afternoon, Saturday evening and Tuesday evening (Dec. 30 and 31, Jan. 3). His program will consist of Mozart's “Jupiter” Symphony; the Lyrici Suite in orchestral form by Alban Berg, which will be heard for the first’s time at these concerts; Debussy Nocturnes — Clouds, Festivals, Sirenes — in the last of which the New England Conservatory Chorus will assist; and Ravel’s Bolero. Mr. Ansermet will also conduct the “Open Rehearsal” on Jan. 5 in preparation for his last pair of concerts in Boston on the following days. [...]"

Le concert de l'après-midi du 30 décembre 1955 fut diffusé en direct sur WBGH-FM, puis rediffusé partiellement les jours suivants, avant tout sur WBGH-FM.

Dans le «The Boston Sunday Globe» du 31 décembre 1955, en page 8, Cyrus DURGIN - chroniqueur musical très connu, décédé prématurément en 1962 - commentait le concert du 30 décembre sous le titre «Boston Symphony Orchestra - Ansermet guest conductor»:

"[...] It was a great pleasure yesterday afternoon to hear the excellent Swiss Musician, Ernest Ansermet, again at Symphony Hall as guest conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. As we have known from his first visit in the season of 1948-1949, and his longer stay in 1951-52 during the illness of Charles Munch, he is a conductor of technical prowess and much delicacy and imagination as interpreter. The gifts which we had come to know in years past again were abundantly evident yesterday.

He offers us, this week, no new music in the sense of recent creation, but the massed strings version of three movements from the Alban Berg Lyric Suite is new to the Symphony concerts. As Mr. Ansermet has stated, and with emphasis, he does not esteem the 12-tone system of musical fabrication, but he does regard these Berg pieces as music of beauty. He is quite correct. Strangely, though the composer worked them out faithfully according to 12-tone rules, the over-all effect is of emotional communication, certainly of much beauty of sound.

But just as strangely, the worth of the Lyric Suite, in this amplified scoring, lies in a comparative style and harmony, melody and timbre, which is very close to Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night, a work originally created more than 50 years ago. To be sure, Berg went farther out of tonality and into organizational dissonance than did Schoenberg of 1899, but the emotional suggestion is a good deal the same. This is especially true of Berg’s first and third num bers, for the second, that vague allegro of much buzzing and little residue, is the least of the three numbers.

Some in yesterday afternoon’s audience liked the Lyric Suite excerpts, some as evidently did not. But it was good to hear them, for, as one elder listener said: “They may not be easy to take, but they are challenging”.

Viennese “Jupiter”

Mr. Ansermet conducted Mozart's great Jupiter Symphony with a sustained line of rhythm and architecture, and a softness of outline almost Viennese. The reduced orchestra sounded full and rich, and also relaxed. There was no forcing, either of sound or emphasis, in Mozart or any other piece of the afternoon.

The Debussy Nocturnes were marvelously mellow and evocative, although Mr. Ansermet asked from the chorus a biger volume of sound than one might have expected in so evanescent a score. As the orchestra played with extraordinary clarity and pure colors, so did the girls’ chorus sing.

It was interesting to observe the Ansermet performance of that much-overworked Ravel hit, Bolero. From first to last it was all musical, a long and finely graduated crescendo, and the big bang at the end was in proportion. Surely this performance put in the best light what has become none too fascinating a score. Let me here also enter my personal commendation of the valiant playing of the snare drum part, so long and reiterative, by Harold Farberman.

Mr. Ansermet was most cordially greeted by the Friday subscribers. He, in turn, at every opportunity shared the applause with the orchestra.

Next week Mr. Ansermet will conduct Bartoks Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta; Stravinsky’s Symphonies for Wind Instruments (first time at these concerts), and the D Minor Symphony of Cesar Franck. [...]"

En présentation de la deuxième série de concerts:

"[...] Ernest Ansermet to Conduct Premiere of Stravinsky’s Symphonies for Winds

Ernest Ansermet, completing his stay of two weeks as guest conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Symphony Hall, will lead the concerts next Tuesday evening and next Friday afternoon and Saturday evening. There will be an open rehearsal on Thursday evening, Jan. 6, under the direction of Mr. Ansermet.

The program for Tuesday will consist of Mozart’s "Jupiter" Symphony; Berg's Lyric Suite; Debussy's three Nocturnes — Cloudy Festivals, Sirens — (with a female chorus of the New England Conservatory participating in Sirens) and Ravel's Bolero.

At the concerts of Friday and Saturday Bartok's Music for String Percussion and Celesta will open the program. Stravinsky’s Symphonies for Wind instruments will have its first performance at these concerts. The concluding number will be the Symphony in D minor by Franck. [...]" cité du «The Boston Sunday Globe» du 1er janvier 1956 en page 29.

Dans la meme page du «The Boston Sunday Globe», sous le titre «More About Ansermet’s Views on Music in 12-Tone System», Cyrus Durgin exposait plus en détails les considérations d'Ernest Ansermet sur la musique dodécaphonique: une comparaison avec le communisme n'était pas sans déplaire dans certains milieux des USA de cette époque, qui n'appréciaient ni la musique dodécaphonique, ni le communisme...

"[...] «The strict 12-tone system in music is like Communism, a ready-made order for those who are confused or lost, who do not know what to do or where to turn. Many younger composers today do not know what style to adopt, and the 12-tone system offers them a haven in which to work, for the rules are thorough and they cannot be accused of sounding old-fashioned.

« So with people dissatisfied with their own society. The Communists say to them: ‘Here is a complete system of social justice, all you have to do is conform to the rules‘.

His Analogy

So declared Ernest Ansermet, the Swiss currently guest conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, over a Turkish cigarette in the Green Room at Symphony Hall after rehearsal last Thursday morning. He did not add that both the 12-tone system and Communism, in this analogy, are attractive to confused and lost people because there is no longer any possibility of individual thought and responsibility, but I gathered that was his drift.

He was speaking half in fun, half seriously in his analogy, but it was obvious he dislikes both systems intensely. Yet he does believe that selective use of some elements of the 12-tone system with conventional tonality can produce musical beauty. That is why he performed, last week, the massed strings version of numbers from Alban Berg's Lyric Suite.

Mr. Ansermet is a man of exceptional intellect, his horizons extending far beyond his own art of music. He was a professor of mathematics before he turned to music professionally. For 10 years he has been writing a book upon the “phenomenology” of music, a work which, he says, will take still two or three years to finish. When it is published, I shall read it with care, for his views are, to make an understatement, most interesting.

The 12-tone system in music is one in which the 12 semi-tones of our scale have equal relationships with each other. This is quite different from the tonal system which was evolved over the years in which the masterpieces (and the junk!) of the past have been created. There music is ruled by greater and lesser relationships of tones and of families of chords. Tonality has definite keys, 12-tone music has none. Tonality includes strong, dissonant chords - “harmonic tensions”, and static chords which make repose. Musical expression works between them. The 12-tone system, taken literally and strictly, is just about all dissonance.

“I have examined the laws of hearing and I have proved by mathematical formulae that the 12-tone system is entirely contrary to those laws. You see objects in perspective, the closer ones bigger to your eye, the distant one smaller. So in music,” continued Mr. Ansermet. “You perceive closer certain tones of greater authority in tonality, lesser ones are perceived more distantly, a sort of hearing perspective. The 12-tone system has no perspective, just as it has no strong and governing bass.”

How It Started

When I suggested that the 12-tone practice of having to make a melody out of a “tone-row” end putting in each of the dozen tones before you can repeat any of them, is sheerly mechanical, the conductor agreed.

“It is mechanical, but if you ignore that rule, at once you begin to return to tonality, and the men who believe in the 12-tone system forbid any suggestion of traditional tonality.

“The 12-tone system began because, after Wagner’s “Tristan and Isolde,” which has extremely chromatic harmony and rapid changes of key, some German composers felt that the language of music as they knew it was worn out. Reger, for example, tried to renew it by going back to counter point but that was not enough. Others, notably Arnold Schoenberg, thought they could renew the musical materials by this system of free relationships among the 12 tones of the scale. That is not a natural but a fabricated, a synthesized, an artificial system.

“The eternal principle in musical development is rationality. Our old tonal system is rational, and the human mind demands rationality, not mere complication. The complication of 12-tone writing is fiercely demanding. I truly believe that Alban Berg, who died at the age of 50, in 1935, was worn out from the mental ravages of working at details of his system.

“But I do believe, and make no mistake, that you can utilize some practises of the 12-tone system, always in a tonal way, and produce music of beauty. Strangely, the Lyric Suite is strict in its 12-tone manipulation, but it is also good music because Berg’s sense of musical beauty in this piece was stronger than his system.” [...]"

Voir plus bas dans cette page pour écouter en ligne deux documents sonores avec Ernest Ansermet et Arthur Honegger s'exprimant sur la musique dodécaphonique.

Comme le(s) document(s) pouvant être écouté(s) ci-dessous est(sont) proposé(s) sur le site de Notre Histoire en « Creative Commons BY-NC-ND» - et conformément aux dispositions de l'article 4.2 des conditions générales de la RTS, propriétaire de ces documents et de tous leurs droits - je peux - en plus de l'écoute - vous le(s) proposer en téléchargement, donc joint(s) à l' enregistrement proposé ici.

Le séjour d'Ernest Ansermet aux USA fit à son retour l'objet d'un seulement très court entrefilet dans la Tribune de Genève du 14 janvier 1956 en page 11:

"[...] Engagé pour plusieurs semaines à la tete de l'orchestre symphonique de Boston, M. Ernest Ansermet vient de remporter une série de succès signalés autant par l'accueil du public que par celui de la presse.

Au cours des deux premières semaines, M. Ansermet a donné, à Boston, les deux programmes suivants, répétés chacun trois fois:

1) Symphonie «Jupiter» de Mozart, «Suite lyrique» d'Alban Berg, «Trois Nocturnes» de Debussy et «Boléro» de Ravel

2) «Suite pour cordes, piano et percussion» de Bela Bartok (*), «Symphonie pour instruments à vent» de Strawinsky et «Symphonie» de César Frank.

M. Ansermet est parti ensuite en tournée à New york (deux concerts), Washington, Newark et Brooklyn. Le chef de l'O.S.R. a en outre fait, à l'Université de Harvard, un exposé de quelques chapitres du livre qu'il est, on le sait, en train d'écrire sur la musique. [...]"

(*) C'est bien entendu la «Musique pour cordes, percussion et célesta» qui est ci-dessus improprement nommée «Suite pour cordes, piano et percussion»

Pour une courte présentation de la «Musique pour cordes, percussion et célesta» de Bela Bartok, voir ma page avec l'extrait de concert du 10 octobre 1956, l'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande étant dirigé par Ernest Ansermet.

L' enregistrement de Boston qui vous est proposé sur cette page vient de la collection privée d'un ami collectionneur des USA qui m'a donné son accord pour vous le proposer ici: je l'en remercie très chaleureusement!

Béla Bartok, Musique pour cordes, percussion et célesta, Sz 106, BB 114, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Ernest Ansermet, 31 décembre 1955

1. Andante tranquillo 07:59 (-> 07:59)

2. Allegro 07:53 (-> 15:52)

3. Adagio 06:41 (-> 22:33)

4. Allegro molto 08:14 (-> 30:47)

Provenance: Provenance: Radiodiffusion, WBGH-FM

que vous pouvez obtenir en...

pour un téléchargement libre, depuis mon site

4 + 2 (**) fichiers FLAC resp. mp3, 2 fichiers CUE (*) et 1 fichier PDF dans 1 fichier ZIP

(*) 1 fichier CUE pour les fichiers décomprimés en WAV et 1 fichier CUE pour les fichiers comprimés FLAC, si votre logiciel peut utiliser directement les fichiers FLAC.

(**) en plus, mp3 de la « RTS Radio Télévision Suisse» mis en écoute ci-dessous, voir l'article 4.2 des conditions générales de la RTS, propriétaire de ces documents et de tous les droits - pour plus de détails.

Ernest Ansermet et Arthur Honegger s'expriment sur la musique dodécaphonique

Comme le(s) document(s) pouvant être écouté(s) ci-dessous est(sont) proposé(s) sur le site de Notre Histoire en « Creative Commons BY-NC-ND» - et conformément aux dispositions de l'article 4.2 des conditions générales de la RTS, propriétaire de ces documents et de tous leurs droits - je peux - en plus de l'écoute - vous le(s) proposer en téléchargement, donc joint(s) à l' enregistrement proposé ici.

a) Musique moderne, Ernest Ansermet, 12 novembre 1951:

"[...] Pour le chef d'orchestre Ernest Ansermet, la musique dodécaphonique telle que l'ont conçue les compositeurs de l'Ecole de Vienne (Schoenberg, Weber, Berg) n'a pas d'avenir.

Il estime que cette musique étant basée sur un théorie nouvelle est hermétique et ne peut pas être compréhensible. L'histoire de la musique montre qu'elle a toujours été une évolution, créant des champs d'expression nouveaux. Or c'est une erreur de croire qu'il faut en changer pour créer de nouvelles techniques d'écriture de manière délibérée.

Les oeuvres de compositeurs contemporains tels Stravinski, Bartok, Frank Martin ou Honegger ont, elles, un avenir, parce qu'elle ne détachent pas d'une évolution naturelle et inconsciente. [...]" cité de cette page du site de la Radio Télévision Suisse.

Cliquer sur la flèche - resp. le pictogramme pause - à gauche pour démarrer - resp. arrêter - l'écoute, saisir le curseur avec la souris et le positionner au minutage désiré pour écouter / réécouter le document à partir d'un endroit donné.

b) Ernest Ansermet et Arthur Honegger, 30 mars 1947:

"[...] Le compositeur Arthur Honegger et le chef d'orchestre Ernest Ansermet débattent des raisons pour lesquelles le public délaisse les oeuvres de musique contemporaine.

Pour tous les deux, le caractère expérimental des musiques dodécaphoniques, notamment, a rebuté tant les interprètes que le public. La recherche purement technique en a fait une musique pour professionnels. Cependant, pour Honegger, ces recherches ont enrichi le vocabulaire musical. Charge maintenant aux compositeurs d'absorber ce langage pour le transmettre au public. [...]" cité de cette page du site de la Radio Télévision Suisse.

Cliquer sur la flèche - resp. le pictogramme pause - à gauche pour démarrer - resp. arrêter - l'écoute, saisir le curseur avec la souris et le positionner au minutage désiré pour écouter / réécouter le document à partir d'un endroit donné.